|

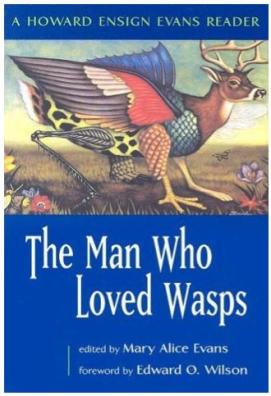

| The Man Who Loved Wasps (Image source: Amazon) |

On a balmy Saturday morning in my hometown I drew out from my collection a tiny book with an astonishing cover page illustration of an antelope’s head and a body comprising of various species of wasps and even birds. Tiny books have most often disappointed me not because of the lack of intellect emanating from the pages, but because more often so much ground is covered within pages so few! So when I got my copy of this book I was skeptical and was wondering if this book will be like some of its tiny predecessors within my library. One book which had been an exception to this case was Dog Man, which was just the right size for the breadth it covered, for a few more pages would have rendered it repetitive. The tile The Man Who Loved Waspsattracted me like a wasp to nectar. It would have made a good companion to Life on Air.

And what a book this has been! It is a collection of essays probably by both Mary Alice Evans and her husband Howard Ensign Evans. It is full of rich and wonderful anecdotes from the insect kingdom, chiefly from the empire of wasps. But more than being just a random assemblage of essays, each chapter is a treatise on a variety of topics, people, insects and birds. Within the pages also figures the sad story of man deliberately destroying the natural habitat with caution thrown to the wind. In the first chapter titled Discovering Life on Earth the author, Howard, poignantly brings out the vagaries of ‘human’ spirit by writing “in a culture obsessed by with comfort, it is doubtless simpler to look at the sterile Martian rocks on television than to become one’s own astronaut, picking one’s way across the incredible plains and forests of Earth”. And in one of the chapters strikingly brings forth the point that we are spending billions of dollars for finding life on other planets, all the while destroying life on Earth! The human, alas, couldn’t have evolved worse.

One interesting story from the book concerns the elephant Jumbo bought by P.T. Barnum from the London Zoo. He was fatally wounded by a locomotive and was later mounted after its hide was stuffed and the heart sold off. And I couldn’t help being amused by the fact that the harmless bumblebee is able to achieve and maintain a temperature 0f 30 degree Celsius by vibrating its muscles without moving the wings even when it is freezing outside. But the most interesting chapter is eerily titled The Intellectual and the Emotional World of the Cockroach. It is abound with experiments which were successful in teaching them complex pathways inside a caged. And how, apparently, when the head is cut off they die only because of starvation and even in beheaded state are able to respond to external stimuli and learn! And how the roach Gromphadorhina Portentosa “not only produces an odor but makes a loud, hissing sound when disturbed”.

Also covered are a lot of great pioneers and their works and lives in this lesser known field of insects and plants. The most thought provoking however was the one which discussed, briefly though, the concept of sociobiology. A lot of social conceptsbelieved by humans to be uniquely theirs have already been there since millions of years in lot insects and animals and how ants already have been practicing sacrifice for the larger community.

There are books which are to be read and those which are to be bought, and this one belonged to the latter category. A must have for anyone remotely interested in the realliving world. However it made me reflect on our actions and their irreversible impact on the surroundings. Over billions of years the living life has evolved, while within a few hundred years the savage butchery has begun at the hands of an ‘evolved’ animal. The gene is much more intelligent than the brain.