|

| Walking with the Comrades |

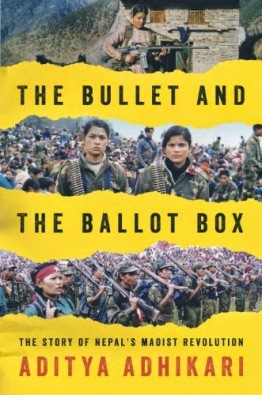

It was Aditya Adhikari’s book which got me hooked onto the ways of the Maoist rebels in the subcontinent. ‘Hello Bastar‘ was one popular book about them but somehow the red bold-face font never made the book cover serious enough to be considered. Well, I am not judging a book by its cover but only ‘not picking’ a book based on its cover. Cover arts do surely add to the enigma of an unread book, hiding all the mysteries of its pages by a plain sheath of artwork.

First things first – this did not turn out to be a book. On Amazon.com it is being sold by Hamish Hamilton (a Penguin imprint) and states that it has 240 pages. However, at the top it states it has 144 pages – don’t know what’s wrong with Amazon here. Amongst so many reviews of it there is not even one person who noticed this difference comes as a disappointing surprise, or was I the only one who got a wrong copy? The actual length of the book is around 30-40 pages. And the entire content is a rip-off from an Outlook India article freely available on University of Pennsylvania website. I wrote to Amazon and they readily refunded my money and topped my account to offset any inconvenience caused. Yes, their customer service was really good and responsive.

So, in essence, I am reviewing an article, not an actual book. Read it for free here.

The contradictions of Dantewada, a Maoist ‘infested’ district, are brought out starkly – “it’s a border town smakck in the heart of India“, “police wear plain clothes and the rebels wear uniforms“, “villages are empty, but the forest is full of people“. The struggles of tribal people have always been there against encroachment on their turf, “it’s convenient to forget that tribal people in central India have a history of resistance that predates Mao by centuries“. Their fight against the Corporate Giants is a task uphill, unmatched by the difficulties of the uneven unyielding terrain. These Corporates are funding schools, universities, hospitals and various other ‘welfare’ schemes, which the author rightly dissects as “creeping, innocuous ways mining corporations enter our imaginations: the Gentle Giants Who Really Care. It’s called CSR, corporate social responsibility“. Economic growth rate which “leaves economists breathless” is what is plucking these tribal people from the heartlands of their homes to roadside shanties and settlements. Growth for whom? Growth for the greedy, death for the needy.

The author travels to the forests and lives with them for days together to understand their way of living, their morals, their struggles, and most importantly, their dream of leading a simple unhinged life. She meets lot of senior comrades who were involved in grassroots revolution from the beginning. Like Comrade Venu, who was “in one of the seven armed squads that crossed the Godavari from Andhra Pradesh and entered the Dandakaranya forest in June 1980, thirty years ago. He is one of the original forty-niners. They belonged to the People’s War Group (PWG), a faction of the Communist Party of India (Marxist – Leninist)“. She doesn’t go much into history of how Naxalism started and the Naxalbari movement. The various modes in which the Indian State has tried to suppress this movement makes one think of the brouhaha about morality and its impending impact on action – “Mahendra Karma, founder of Salwa Judum – were conferred the status of Dwij, twice-born, Brahmins. As a part of the Hindutva drive the names of villages were changed in land records, as a result of which most have two names now, people’s names and government names. Innar village became Chinnari. On voters’ lists tribal names were changed to Hindu names (Massa Karma became Mahendra Karma). Those who did not come forward to join the Hindu fold were declared ‘Katwas’ (untouchables), who later became the natural constituency for the Maoists“. PWG’s two historical successes are chronicled: rise in the price for tendu leaves (used to make beedis) and the second against Ballarpur Paper Mills. But these were worldly gains; that they can become united against atrocities was a triumphant moment.

That “Tata Steel and Essar Steel were the first financiers of the Salwa Judum” comes as the rudest shock from this book/article. She refers to a report of Ministry of Rural Development. That report clearly states, “A civil war like situation has gripped the southern districts of Bastar, Dantewara and Bijapur in Chattishgarh. The contestants are the armed squads of tribal men and women of the erstwhile Peoples War Group now known as the Communist Party of India (Maoist) on the one side and the armed tribal fighters of the Salva Judum created and encouraged by the government and supported with the firepower and organization of the central police forces. This open declared war will go down as the biggest land grab ever, if it plays out as per the script. The drama being scripted by Tata Steel and Essar Steel who wanted 7 villages or thereabouts, each to mine the richest lode of iron ore available in India“. Frontline did a story on that, and the Tatas soon came up with an explanation. Counterview offers an insight into the economies of how farmers become unorganized industrial labour in Maoist-lands (Felix Padel is great-great-grandson of Charles Darwin). The hand-in-glove approach of mainstream media is dissected with the detachment of a surgeon, “you might have read about (an attack on Salwa Judum) – something like ‘Maoists attacked the relief camp set up by the state government to provide shelter to the villagers who had fled from their villages because of terror unleashed by the Naxalites’“. The author’s brilliant piece on Capitalism should be and must be read (and then there are half-baked fact-based counterpoints).

However, no movement however pious is bereft of human shortcomings, the lure of violence and instant justice as amazingly documented here. There is discontent amongst the tribal people with regards to Maoist overtures. And this is what was used for the creation of Salwa Judum: discontent.

The article (sorry, book!) makes for a decent read on what the Maoists are suffering for and fighting for.